in this one, Torben talks about the “benefits” of external/tension based training like weight training and kettlebells, whether is it good or bad to have different teachers, “substitute methods”, the importance of doing what you love in life among other things.

Blast from the Past (X): Lao Tsu

I spend some time today reading Lao Tzu quotes, and have managed them in a tidy order so they make a poem of sorts. It deals with what I consider the timeless core of all mystical traditions: The meditative practice – the catch-all tool of the mystic that cuts to the root of mental/spiritual illusion and suffering.

“My teachings are older than the world.

He who controls others may be powerful, but he who has mastered himself is mightier still.

The inner is foundation of the outer. If you correct your mind, the rest of your life will fall into place.If you are depressed you are living in the past.

If you are anxious you are living in the future.

If you are at peace you are living in the present.

Hope and fear are both phantoms that arise from thinking of the self. When we don’t see the self as self, what do we have to fear?

free from desire, you realize the mystery.

caught in the desire, you see only the manifestations.

If you don’t realize the source, you stumble in confusion and sorrow.

If you realize that all things change, there is nothing you will try to hold on to.

He who clings to his work will create nothing that endures.If you search everywhere, yet cannot find what you are seeking, it is because what you seek is already in your possession.

To hold, you must first open your hand. Let go.

Stop leaving and you will arrive.

Stop searching and you will see.

Stop running away and you will be found.

Stop thinking, and end your problems. Let your heart be at peace.

the unwanting soul sees what’s hidden.

Stillness reveals the secrets of eternity.

To the mind that is still, the whole universe surrenders.Muddy water, let stand, becomes clear. Do you have the patience to wait until your mud settles and the water is clear?

Be still

Become totally empty.

Quiet the restlessness of the mind

As soon as you have made a thought, laugh at it.

Just remain in the center; watching. And then forget that you are there.

Only then will you witness everything unfolding from emptiness.”

Lessons from the Masters: Interview with Torben Bremann (part 3)

This is the third part of my interview with Torben from 2018. This time, Torben talks a bit about taking your martial practice into your civil life, character building and emotional balance.

Blast from the Past (VIII): Vladimir Janda

Seeing as one of my goals (as written in the previous post) is…

Promote superior resistance to wear and tear and common injuries.

– Janda’s upper crossed/lower crossed/layer syndrome

…I want to write a little intro to Janda and his work. Hopefully to the benefit of those of you who read my log.

Vladimir Janda, a Czechoslovakian neurologist and exercise physiologist categorized muscles as being either tonic/postural or phasic.

A short overview of the most important muscles in each category:

Tonic/postural muscles (prone to tightness or shortness)

Sub occipitals. (small muscles in your upper neck, below the skull)

SCM

Trap 1

Levator scap

Pec major/minor

Biceps

Hip flexors (psoas, iliacus, rectus femoris, satorius, tensor etc.)

Lower back extensors

adductors

Piriformis

Hamstrings

Calf Muscles

Phasic muscles(prone to weakness or inhibition)

Neck flexors (Longus coli and capitis)

Serratus anterior

Mid-back (Rhomboids, lower traps)

Deltoid

Triceps

Glutes (max, med, min)

Abdominal muscles

Quad (minus rectus femoris, which is a tonic hip flexor)

These dysfunctional patterns of tightness/weakness manifest what Janda called…

– upper crossed syndrome (cervical hyperlordosis, thoracic hyperkyphosis) and

– lower crossed syndrome (anterior tilt of the pelvis/hyperlordosis of the lower back)

…(and what the rest of us might just call poor posture) due to the ‘crossing’ junctures resulting from the tonic and phasic muscles at these locations:

Upper and Lower crossed together:

Addressing the tonic/phasic pattern is really good stuff for unwinding foundation issues of many of the problems we have in our musculo-skeletal system.

As you can see from the list, it fits very well with all the pre/rehab advice you get in a clinic or around the web for what ails you in different parts of your body: Do glute activation, stretch hip flexors, stretch the pecs, do pushups for the serratus, work on extension of the thoracic spine, stretch the piriformis, do more one-legged work to get hip-stability (glut. med.) etc. etc.

By adressing the muscles in these categories (activate the phasic muscles, stretch/mobilize the tonic ones) you will prevent, cure or at least influence virtually ALL musculo-skeletal problems and pains in a postive way, since you are dealing with optimization of fundamental muscular patterns in the body.

A ‘perfect’ routine should address this and at least the muscles involved in upper and lower crossed syndrome. It is something I aspire to do in my own minimalist program. How it does that is probably something I’ll elaborate on in another post later.

Health: Biomarkers – 10 Determinants of Aging You Can Control (Clarence Bass)

Biomarkers (Simon & Schuster, 1991) has stood the test of time impressively, says Tufts University Health & Nutrition Letter (May 2006). “While research has of course added to our knowledge about all 10 of the biomarkers described in the book, the basic lessons still hold true today.”

For many years, aerobic exercise was thought to be practically synonymous with good health. Weight training or bodybuilding was considered mainly cosmetic. That changed with the publication of Biomarkers by William Evans, PhD, and Irwin H. Rosenberg, MD, professors of nutrition and medicine, respectively, at Tufts University. Strength training took its rightful place as an equal partner with aerobics. Moreover, strength training became the senior partner for taking the worry out of aging.

The book features landmark studies at the USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA) showing that people past middle age are able to gain muscle and increase strength by as much as 200%. What’s more, muscle and strength were found to be the key controllable physiological factors associated with aging. One 93-year-old study participant observed: “I feel as though I were 50 again…Pills won’t do for you what exercise does!”

The HNRCA was and is located at Tufts University. Evans was the Chief of the Human Physiology Laboratory at the HNRCA; Rosenberg was the Director and subsequently became dean of Tufts’ Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. Both have moved on to other posts. Quite appropriately, Tufts University Health & Nutrition Letter (May 2006) includes a Special Supplement assessing how well the 15-year-old program for controlling the aging process has stood the test of time.

“The bottom line of Biomarkers remains as true now as then,” they conclude: “Exercise is the key to a healthy and rewarding old age. Even for the frail elderly—and this is still a bold concept—a regular exercise program can have a strong positive health impact. A combination of regular aerobics, flexibility and strength training is the best strategy for retarding—even reversing—the effects of aging on the 10 biomarkers the authors identify.”

Biomarkers

To paraphrase Satchel Paige, the ageless baseball pitcher, biomarkers are those things that tell how old you would be “if you didn’t know how old you was.” In Biomarkers, Evans and Rosenberg isolated the following signposts of vitality that can be altered for the better by changes in lifestyle:

1) Muscle Mass

2) Strength

3) Basal Metabolic Rate

4) Body Fat Percentage

5) Aerobic Capacity

6) Blood-sugar Tolerance

7) Cholesterol/HDL Ratio

8) Blood Pressure

9) Bone density

10) Ability to regulate Internal Temperature

Significantly, all 10 biomarkers can be revived or improved through strength training.

To help people understand how strength training affects the biomarkers, the authors coined the term “sarcopenia” to describe an ailment that affects many old people and deprives them of their independence. “Sarco” refers to flesh, “penia” means a reduction in amount. So sarcopenia describes an overall weakening of the body caused by a change in body composition in favor of fat and at the expense of muscle.

Evan and Rosenberg say that the first biomarker, muscle mass, is responsible for the vitality of your whole physiological apparatus. Muscle mass and strength, the second signpost, are our primary biomarkers. They’re the lead dominoes, so to speak. When they start to topple, the other biomarkers soon follow. On the other hand, when muscle mass and strength are maintained, the other indicia are likewise maintained. That is where strength training comes to our aid. Aerobic exercise and diet are important, but strength training, according to the authors, is pivotal if you want to stay young longer.

Fifteen Years Later

“Since the publication of Biomarkers, subsequent research has continued to support [the authors’] basic premise,” says the Tufts Supplement. Exercise and diet are the keys to successful aging.

Let’s look at a few points of special interest highlighted in the Tufts Supplement.

First, the average middle-aged person may be inclined to focus on losing or maintaining bodyweight. That’s not good enough. Your target should be body composition, improving your ratio of muscle to fat. The key is to minimize “biologically inactive” fat tissue and maximize “biologically active” muscle mass. “People with a greater ratio of muscle to fat enjoy a higher metabolism and don’t have to worry as much about gaining weight or about how much they eat—that active tissue burns more calories.”

Conventional wisdom that muscle mass and strength decline with age, accelerating after 45, is wrong. “If you use your muscles frequently, you can maintain their strength. But if you push your muscles to the limit of their capacity by exercise, you can actually increase their strength—no matter what your age…The fact is that you can regain muscle mass and strength, no matter your age or what shape you’re in now.”

One more key point regarding strength training, one often over looked: “To be effective, strength training must be progressive, or you won’t get full benefit; as the intensity of your activity increases, so will your strength.” In short, don’t rest on your laurels; keep trying to improve, slowly and carefully, but persistently.

As we say above, aerobic exercise is important, but strength training is central to staying young longer. In point of fact, strength training increases the effectiveness of aerobic exercise, especially for older athletes. Here’s why, as explained in the Tufts Supplement.

“While both young and older people benefit from regular aerobic exercise—the kind that makes you huff and puff—the positive changes in older people come almost entirely in the muscles’ ability to utilize oxygen (oxidative capacity), rather than in the heart or cardiovascular system.” That’s another reason why you need the added muscle mass which comes from strength training. “When you build muscle, you create more muscle cells to consume oxygen. The more demand for oxygen from your muscles, the greater your utilization of oxygen and your aerobic capacity.”

Flatten Your Health Span

The ultimate goal of controlling your biomarkers is to extend your years of good health and compress your years of decline. By making positive changes in your biomarkers through a combination of exercise, especially strength training, and eating right, you can “prolong vitality, postpone disability, and prevent the development of sarcopenia.” The latter is very important, according to the Tufts Supplement. The price of sarcopenia is “loss of balance, reduced mobility and the frailty so often seen in the elderly.” Making the right lifestyle changes early on can postpone—sometimes for decades—what Evans and Rosenberg call the Disability Zone. “You can greatly improve your odds of approaching the ideal: a health span that almost matches your life span.”

(Originally posted at: http://cbass.com/Biomarkers.htm)

Lessons from the Masters: Interview with Torben Bremann (part 2)

This is the second part of the interview I did with Torben. This time around Torben talks about why and how you ask questions, the “skill” of it, and the traditional and western approach to development.

Lessons from the Masters: The Five Levels of Skill in Chen Style Taijiquan (Chen Xiaowang)

by Chen Xiao Wang translated by Tan Lee-Peng, Ph.D.

Learning taijiquan is in principle similar to educating oneself; progressing from primary to university level, where one gradually gathers more and more knowledge. Without the foundation from primary and secondary education, one will not be able to follow the courses at university level. To learn taijiquan one has to begin from the elementary and gradually progress to the advanced stage, level by level in a systematic manner. If one goes against this principle thinking he could take a quick way out, he will not succeed. The whole progress of learning taijiquan, from the beginning to achieving success consists of five stages or five levels of martial/combat skill (kung fu). There are objective standards for each level of kung fu. The highest is achieved in the fifth level.

Learning taijiquan is in principle similar to educating oneself; progressing from primary to university level, where one gradually gathers more and more knowledge. Without the foundation from primary and secondary education, one will not be able to follow the courses at university level. To learn taijiquan one has to begin from the elementary and gradually progress to the advanced stage, level by level in a systematic manner. If one goes against this principle thinking he could take a quick way out, he will not succeed. The whole progress of learning taijiquan, from the beginning to achieving success consists of five stages or five levels of martial/combat skill (kung fu). There are objective standards for each level of kung fu. The highest is achieved in the fifth level.

The standard and martial skill requirements for each level of kung fu will be described in the following sections. It is hoped that with these, the many taijiquan enthusiasts all over the world will be able to ‘assess’ on their own their current level of attainment. They will then know what they need to learn next and advance further step-by-step.

The First Level of Kung Fu

In practising taijiquan, the requirements on the different parts of the body are: keeping a straight body; keeping the head and neck erect with mindfulness at the tip of the head as if one is lightly lifted by a string from above; relaxing the shoulders and sinking the elbows; relaxing the chest and waist letting them sink down; relaxing the crotch and bending the knees. When these requirements are met, one’s inner energy will naturally sink down to the dan tian.

Beginners may not be able to master all these important points instantly. However, in their practice they must try to be accurate in terms of direction, angle, position, and the movements of hands and legs for each posture. At this stage, one need not place too much emphasis on the requirements for different parts of the body, appropriate simplications are acceptable. For example, for the head and upper body, it is required that the head and neck be kept erect, chest and waist be relaxed downward, but in the first level of kung fu, it will be sufficient just to ensure that one’s head and body are kept naturally upright and not leaning forward or backward, to the left or right. This is just like learning calligraphy, at the beginning, one need only to make sure that the strokes are correct. Therefore, when practising taijiquan at the beginning, the body and movements may appear to be stiff; or ‘externally solid but internally empty’. One may find oneself doing things like: hard hitting, ramming, sudden uplifting and or sudden collapsing of body or trunk. There may be also be broken or over-exerted force or jin. All these faults are common to beginners. If one is persistent enough and practices seriously everyday, one can normally master the forms within half a year. The inner energy, qi, can gradually be induced to move within the trunk and limbs with refinements in one’s movements. One may then achieve the stage of being able to use external movements to channel internal energy’. The first level kung fu thus begins with mastering the postures to gradually being able to detect and understand jin or force.

The martial skill attainable with the first level of kung fu is very limited. This is because at this stage, one’s actions are not well coordinated and systematic. The postures may not be correct. Thus the force or jin produced may be stiff, broken, lax or on the other hand too strong. In practicing the routine, one’s form may appear hollow or angular. As such one can only feel the internal energy but is not able to channel the energy to every part of the body in one go. Consequently, one is not able to harness the force or jin right from the heels, channel it up the legs, and discharge it through command at the waist. On the contrary , the beginners can only produce broken force that ‘surge’ from one section to another section of the body. Therefore the first level kung fu is insufficient for martial application purposes. If one were to test one’s skill on someone who does not know martial arts, to a certain extent they can remain flexible. They may not have mastered the application but by knowing how to mislead his opponent the student may occasionally be able to throw off his opponent. Even then, he may be unable to maintain his own balance. Such a situation is thus termed “the 10% yin and 90% yang; top heavy staff”.

What then exactly is yin and yang? In the context of practising taijiquan, emptiness is Yin, solidity is yang; gentleness or softness is yin, forcefulness or hardness is yang. Yin and yang is the unity of the opposites; either one cannot be left out; yet both can be mutually interchanged and transformed. If we assign a maximum of 100% to measure them, when one in his practice can attain an equal balance of yin and yang, he is said to have achieved 50% yin and 50% yang. This is the highest standard or an indication of success in practicing taijiquan. In the first level of skill in kung fu, it is normal for one to end up with ‘10% yin and 90% yang’. That is, one’s quan or boxing is more hard than soft and there is imbalance in yin and yang. The learner is not able to complement hard with soft and to command the applications with ease. As such, while still at the first level, learners should not be too eager to pursue the application aspect in each posture.

The Second Level of Kung Fu

The level starting from the last stage of the first level when one can feel the movement of internal energy or qi to the early stage of the third level of kung fu is termed as the second level of kung fu. The second level of kung fu involves further reducing shortcomings such as: stiff force/jin produced while practising taijiquan; over- and under-exertion of force as well as movements which are not well coordinated. This is to ensure that the internal energy/qi will move systematically in the body in accordance with the requirements of each movement. Eventually, this should result in smooth flowing of qi in the body and good coordination of internal qi with external movements.

After acquiring the first level of kung fu, one should be able to practise with ease according to the preliminary requirements of the movements. The student is able to feel the movement of internal energy. However, the student may not be able to control the flow of qi in the body. There are two reasons for this: firstly, the student has not mastered accurately the specific requirements on each part of the body and their coordination. As an example, if the chest is relaxed downward too much, the waist and back may not be straight, or if the waist is too relaxed then the chest and rear may protrude. As such, one must further strictly ensure that the requirements on each part of the body should be resolved so that they move in unison. This will enable the whole body to close or unite in a coordinated manner (which means coordinated internal and external closing/union. Internal closing implies coordinated union of heart and mind, of internal energy and force, tendons and bones. External closing/union of movements implies coordinated closing of hands with legs, elbows with knees, shoulders with hips). Simultaneously, there should be an equal and opposite closing movement of another part of the body and vice versa. Opening and closing movements come together and complement each other. Secondly, while practising one may find it hard to control different parts of the body all at once. This means one part of the body may move faster than the rest and result in over-exertion of force; or a certain part may move too slowly or without enough force, thus resulting in a under-exertion of force. These two phenomena both contradict the principle of taijiquan. Every movement in Chen style taijiquan is required not to deviate from the principle of the ‘spiralling silk force’ or chan-si jin. According to the Theory of Taijiquan, ‘the chan-si-jin originates from the kidneys and at all times is found in every part of the body’. In the process of learning taijiquan, the spiralling-silk method of movement (ie. the twining and spiralling method of movement) and the spiralling-silk force (ie. the inner force produced from the spiralling-silk method of movement), can be strictly mastered through relaxing shoulders and elbows, chest and waist as well as crotch and knees and using the waist as a pivot to move every part of the body. Starting with rotating the hands anti-clockwise, the hands should lead the elbows which in turn leads the shoulders which then guide the waist (the part of the waist corresponding to that side of the should that is being moved. In actual fact the waist is still the pivot). On the other hand, if the hands rotate in a clockwise direction, the waist should move the shoulders, the shoulders move the elbows, the elbows in turn move the hands. For the upper half of the body, the wrists and arms should appear to be gyrating; whereas for the lower portion of the body the ankle and the thigh should appear to be rotating; as for the trunk, the waist and the back should appear to be turning. Combining the movements of the three parts of the body we should visualise a curve rotating in space. This curve originates from the legs, with the centre at the waist and ends at the fingers. In practising the quan, (or the form), if one feels awkward with a particular movement, one can adjust one’s waist and thigh according to the sequence of flow of the chan-si-jin to achieve coordination. In this way, any error can be corrected. Therefore, while paying attention to the requirement on each part of the body to achieve total co-ordination of the whole body, the mastering of the rhythm of movement of the spiralling-silk method and spiralling silk force is a way of resolving conflicts and self-correction for any mistake in practising taijiquan after attaining the second level of kung fu.

In the first level of kung fu, one begins with learning the forms, and when one is familiar with the forms, the student can feel the movement of internal energy in the body. The student may well be very excited and thus never feel tired or bored. However, in entering the second level of kung fu, the student may feel there is nothing new to learn and at the same time misunderstand certain important points. The student may not have mastered these main points accurately and thus find that their movements are awkward. Or, on the other hand, the student may find that he or she can practise the quan smoothly and express force with much vigour but cannot apply them while doing push-hands. Because of this, one may soon feel bored, lose confidence and may give up altogether. The only way to reach the stage where one can: produce the right amount of force, not too hard and not too soft; can change actions at will; and can turn smoothly with ease, is to be persistent and strictly adhere to principles. One has to train hard in the form so that the body movements are well co-ordinated, and with ‘one single movement can activate movements in every part of the body’ , thus establishing a complete system of movements. There is a common saying, ‘if the principle is not clearly understood, consult a teacher; if the way is not clearly visible, seek the help of friends’. When the principles as well as the methods are clearly understood, with constant practice, success will prevail eventually. The Taijiquan Classics state that, ‘everybody can possess the ultimate, if only one works hard.’ And ‘if only one persists, ultimately one should achieve sudden break through’. Generally, most people can attain the second level of kung fu in about four years. When one reaches the state of being able to experience a smooth flow of qi in the body, one would suddenly understand it (the command of qi) all. When this happens, one would be full of confidence and enthusiasm as one goes on practising. One may even have the strong urge to go on and on and wouldn’t feel like stopping!

At the beginning of the second level kung fu the martial art skill attained is about the same as in the first level kung fu. It is not sufficient for actual application. At the end of the second level kung fu one is nearing attaining the third level kung fu, as such the martial skill acquired may be applicable to a certain extent.

The next section introduces the martial skill that should be attainable half-way through the second level kung fu (so are the third, fourth and fifth levels of kung fu in the subsequent sections. They are discussed with reference to the skill attainable in the half-way stage in each level.)

Push-hands and practising taijiquan are inseparable. Whatever shortcomings one has in his quan form will show up as weaknesses during push-hands and thus giving the opponent an opportunity to take advantage of them. Because of this, in practising taijiquan every part of one’s body must be well coordinated with the rest, there shouldn’t be any unnecessary movement. Push-hands requires warding-off, grabbing, squeezing and pressing to be carried out so precisely, so that the upper and lower bodies move in co-ordination and it is thus difficult for opponents to attack[. As the saying goes: ‘No matter how great is the force on me, I should mobilise four ounces of strength to deflect one thousand pounds of force’. The second level of kung fu aims at achieving smooth flowing of qi in the body by correcting the postures so as to reach the stage when qi should penetrate the whole body passing through every joint as if it (qi) is sequentially linked. However, the process of adjusting the postures involves making unnecessary or unco-ordinated movements. Therefore, at this stage, one is unable to apply the martial skill at will during push-hands. The opponent will concentrate on looking for these weaknesses or he or she may win by surprising one into committing all the errors like over-exerting, collapsing, throwing-off and confronting of force. During push-hands, the opponent’s advance will not allow one to have time to adjust one’s movements. The opponent will make use of one’s weak point to attack so that one will lose balance or will be forced to step back to ward off the advancing force. Nevertheless, if the opponent advances with less force and in a slower manner, there may be time or opportunity to make adjustments and one may be able to ward off the attack in a more satisfactory manner. Drawing from the above discussion, for the second level kung fu, whether one is attacking or blocking-off an attack, much effort is needed. Very often, it will be an advantage to make the first move, the one who moves last will be at an disadvantage. At this level, one is unable to ‘forget’ oneself but ‘play along with’ the opponent (ie. not to attack but to yield to the opponent’s movement); unable to grasp an opportunity to respond to change. One may be able to move and ward off an attack but may easily commit errors like throwing-off or collapsing and over-exerting or confronting [the?] force. Because of these, during push-hands, one cannot move according to the sequence of warding-off, grabbing, pressing and pushing down. A person with this level of skill is described as ‘20% yin, 80% yang: an undisciplined new hand.’

The Third Level Kung Fu

‘If you wish to do well in your quan (or form), you must practice to make your circle smaller.’ The steps in practising Chen-style taijiquan involve progressing from mastering big circle to medium circle and from medium circle to small circle. The word ‘circle’ here does not mean the path/trail resulting from movements of the limbs but rather the smooth flowing of the internal energy of qi. In this respect, the third level kung fu is a stage in which one shall begin with big circle and end with medium circle (in the circulation of qi).

The Tiajiquan Classic mentioned that ‘yi and qi are more superior than the forms’ meaning that while practising taijiquan one should place emphasis on using yi (consciousness). In the first level of kung fu, one’s mind and concentration are mainly on learning and mastering of the external forms of taijiquan. While in the second level of kung fu, one should concentrate on detecting conflicts/unco-ordination of limbs and body and of internal and external movements. One should adjust body and forms to ensure a smooth flow of the internal energy. When progressing into the third level kung fu, one should already have the internal energy flowing smoothly: what is required is yi and not brute force. The movements should be light but not ‘floating’, heavy but not clumsy. This implies that the movements should appear to be soft but the internal force is actually strong/sturdy, or there is strong force implied in the soft movements, and the whole body should be well-coordinated and there should not be any irregular movements. However, one should not just pay attention to the movement of qi in the body and neglect the external actions. Otherwise, one would appear to be in a daze and as a result, the flow of internal qi may not only be obstructed but may be dispersed. Therefore, as stated in the Taijiquan Classics, ‘attention should be on the spirit and not just qi, with too much emphasis on qi there will be stagnation (of qi)’.

One may have mastered the external forms between the first and second level kung fu, but he may not have attained co-ordination of the external with internal movements. Sometimes, due to stiffness or stagnation of the actions, full breathing-in is not possible. On the other hand, without proper co-ordination of the internal and external movements, it is not possible to empty one’s breath completely. Thus, when practising quan one should breath[e] naturally. After entering into the third level kung fu, there is better co-ordination of internal and external movements. As such generally the actions can be synchronized with breathing quite precisely. However, it is necessary to consciously synchronize breathing with movements for some finer, more complicated and swifter actions. This is to further ensure co-ordination of breathing and actions so that it gradually comes on naturally.

The third level of kung fu basically involves mastering the internal and external requirements of Chen-style taijiquan and rhythm of exercise as well as the ability to correct oneself. One should also be able to command the actions with more ease and should also ha[ve] more internal energy (qi). At this level, it is necessary to further understand the combat skill implicit in each quan form and its application. For this, one has to practise push-hands, check on the forms, the quality and quantity of the internal force and expression of the force as well as dissolving of force. If one’s quan form can withstand confrontational push-hands then one must have mastered the important points of the form. He would gain more confidence if he continues to work hard. He may then step up his exercise routine and add in some complementary practice like practising with the long staff, sword or broad sword; spear and pole as well as practising fa jin i.e. expression of explosive force on its own. With two years continuous practise in this manner, generally one should be able to attain the fourth level of kung fu.

With the third level of kung fu, although there is smooth flow of internal qi and the actions are better coordinated, but the internal qi is weaker and the coordination between muscle movements and the functioning of the internal organs is not sufficiently established. While practising alone without external disturbances, one may be able to achieve internal and external coordination. During confrontational push-hand[s] and combat, if the advancing force is softer and slower, one may be able to go along with the attacker and change one’s actions accordingly; grab any opportunity to lead the opponent into a disadvantageous situation[; or] avoid the opponent’s firm move but attack when there is any weakness, manoeuvring with ease. However, once encountering a stronger opponent, the student may feel that his peng jin, i.e. blocking force, is insufficient, and there is a feeling that one’s form is being pressed and about to collapse (this may destroy the unfailing position which is supposed to be never-leaning and never-declining but with all round support), and cannot manoeuvre at will. The student may not achieve what the Taijiquan Classics describe as ‘striking with the hands without them being seen, once they are visible, it is impossible to manipulate’. Even in leading-in and expelling-out the opponent, one [may] feel stiff and much effort is required. As such the skill at this stage is described as ‘30% yin, 70% yang, still on the hard side.’

The Fourth Level Kung Fu

Progressing from the stage with medium circle to that with small circle is required of the fourth level kung fu. This is the stage nearing success and thus is of high level of kung fu. One should have mastered the effective method of training, be able to grasp the important points in the movements; be able to understand the martial/combat skill implicit in each movement; to have smooth flow of the internal energy or qi; and the co-ordination of actions with breathing. However, during practice, each step and each movement of hands should be carried out with a confronting opponent in mind, that is to say, one has to assume that he is surrounded by enemies. For each posture and each form, each part of the body must move in a linked and continuous manner so that the whole body moves in unison. ‘Movements of the upper and lower body are related and there should be a continuous flow of qi with the control being at the waist.’ So that when practising quan, one should carry it out ‘as if there is an opponent although no-one is around’. When actually confronted, one should be brave but cautious, behaving ‘as if there is no-one around though there is someone there.’

The training content (like quan and weapons) is similar to that in third level of kung fu. With perseverance, generally the fifth level kung fu can be reached in three years. In terms of martial skill the fourth level differs much from the third level kung fu. The third level kung fu aims at dissolving the opponent’s force and to get[ting] rid of conflicts in one’s own actions. This is to enable oneself to play the active role and forcing the opponent to be passive. The fourth level kung fu enables one to dissolve as well as express force. This is because at that level, one would have sufficient internal jin, flexible change in yi and qi and a consolidated system of the body movements. As such, during push-hands, the opponent’s attack does not pose a big threat. On contact with the opponent, one can immediately change one’s action and thus disolve the on-coming force with ease, exhibiting the special characteristics of going along with the movements of the opponent but yet changing one’s own actions all the time to counteract the opponent’s action, exerting the right force, adjusting internally, predicting the opponent’s intention, subduing one’s own actions, expressing precise force and hitting the target accurately. Therefore, a person attaining this level of kung fu is described as ‘40% yin, 60% yang; akin to a good practitioner.’

The Fifth Level Kung Fu

The fifth level kung fu is the stage in which one moves from commanding small circle to commanding invisible circle, from mastering the form to executing the form invisibly. According to the Taijiquan Classics, ‘with the continuous smooth flowing of qi, with the cosmic qi moving one’s natural internal qi, moving from a fixed form to invisibility, one realises how wonderful nature is.’ At the fifth level, the actions should be flexible and smooth, and there should be sufficient internal jin. However, it is still necessary to strive for the best. There is the need to work hard day by day until the body is very flexible and adaptable to multi-faceted changes. There should be changes internally alternating between the substantial and insubstantial but these should be invisible externally. Only until then that the fifth level kung fu is achieved.

As regarding the martial skill, at this level the gang (hard) should complement the rou (soft), it (the form) should be relaxed, dynamic, springy and lively. Every move and every motionless instant is in accordance with taiji principle, as are the movements of the whole body. This means that every part of the body should be very sensitive and quick to react when the need arises. So much so that every part of the body can act as a fist to attack whenever is in contact with the opponent’s body. There should also be constant interchange between expressing and conserving of force and the stance should be firm as though supported from all sides.

Therefore the description for this level of kung fu is that it is the ‘only one that plays with 50% yin and 50% yang, without any bias towards yin or yang, and the person who can do this is termed a good master. A good master makes every move according to the taiji principles which demands that every move be invisible.’

After completing the fifth level kung fu a strong relationship has been established between the co-ordination of the mind, contraction and relaxation of the muscles, movements of the muscles and functioning of the internal organs. Even when encountering a sudden attack such co-ordination will not be hampered as one should be flexible to change. Even then, one should continue to pursue further so as to achieve greater heights.

After completing the fifth level kung fu a strong relationship has been established between the co-ordination of the mind, contraction and relaxation of the muscles, movements of the muscles and functioning of the internal organs. Even when encountering a sudden attack such co-ordination will not be hampered as one should be flexible to change. Even then, one should continue to pursue further so as to achieve greater heights.

Development in science is beyond boundary, so is practising taijiquan: one could never exhaust all its beauty and benefits in one’s life time.

(Original source: http://www.shou-yi.org/taijiquan/5-levels-of-skill-in-chen-taijiquan)

Lessons from the Masters: Interview with Torben Bremann (part 1)

(I am getting rid of numbering these posts – there will be a lot of them in the future it seems, and latin numereals aren’t that fun to look at 😉 )

This is the first part of a 2 hour long interview/conversation I did with my teacher and mentor Torben Bremann, covering his take on Taiji and internal martial arts, sharing his thoughts about internal martial art as well as the civil aspects of these arts.

Over the past 30 years he has received thousands upon thousands of hours of one on one teaching from his teachers in the traditions of Chen style taijiquan, Yang style taijiquan, Yiquan and more. For the last 13 years he has been a close student of Master Sam Tam.

In this part, Torben talks a bit about his take on the whole internal vs external debate that always pops up everywhere internal martial arts are talked about, as well as the illusive qi concept.

Health: Relaxation Training and Breathing (Pavel Tsatsouline)

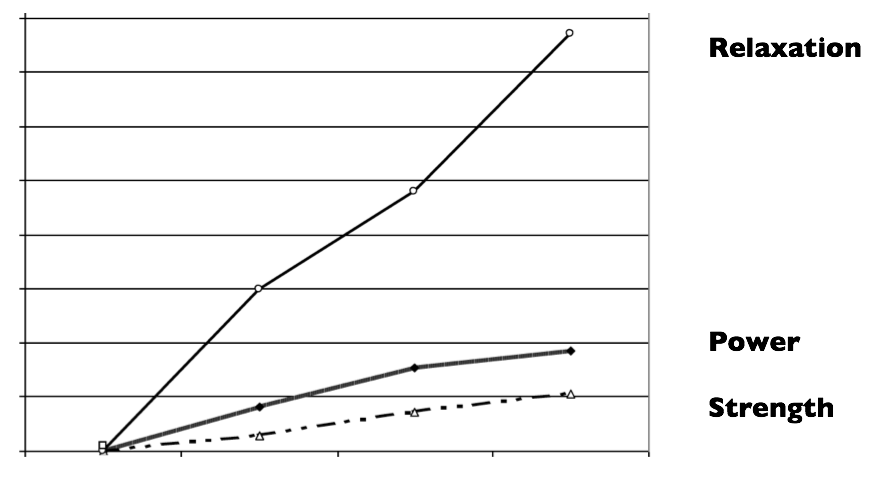

The three lines below follow the improvement in different qualities—strength, power, and the speed of voluntary muscle relaxation—in game athletes from a low intermediate level on the left to advanced on the right:

In 17 out of the 20 sports evaluated by Russian scientists the relaxation ability was more important than either strength or power at the elite level. It was suggested that the strength and power reached by high intermediates (Level I-CMS) are sufficient for reaching world class performance in many events—and further performance growth is made through improved relaxation.

(In case you decide that you are already strong enough after reading this, consider that Russian boxers snatch their bodyweight and teenage girl jumpers casually single leg squat with 40-50kg for sets and reps. These “intermediate” standards will not impress any weightlifter or powerlifter but they are not something that you will reach casually. Yes, you still must be strong first.)

The benefits of muscle relaxation training

Soviet sports scientists realized the necessity to improve voluntary muscle relaxation back in the 1930s.

Research in the decades that followed revealed the benefits of training it to be powerful and many:

- Increases speed

- Significantly correlates with reactive ability and explosive strength

- Increases endurance—without compromising speed-strength

- Improves coordination

- Decreases the motor reaction time

- Accelerates recovery after training

- Reduces injuries induced by fatigue

- Lowers overtraining odds

- Improves special work capacity and athletic performance

- Has a favorable effect on the function of inner organs

- Strengthens resistance to physical and psychological stress

- Increases athletic longevity

Traditionally, athletic training has been a zero sum game. You have a limited “pie” of time and recovery and whenever you give one quality a bigger “slice”, you have to take some away from another quality. Relaxation training is philosophically opposite: it builds a bigger pie. Not only training this quality does not take anything away from others—it gives a bump to other attributes plus accelerates recovery to enable you to train longer and harder (or just to have more energy and feel better).

How do elite athletes and soldiers react to extreme stimuli?

A high performing unit—machine, animal, or human—comes with well-tuned “on” and “off” switches (technically speaking, “a balance of excitation and inhibition in the CNS”).

A less effective one has its “on” switch stuck.

Any voluntary movement starts with excitation of the appropriate nerve cells in the brain. They in turn signal the muscles to contract. Inhibition of these neurons causes the muscles to relax. If the CNS is overexcited or inhibition (the “off” switch) is not powerful enough, some of these neurons will remain turned on and keep commanding the muscles to contract at times when they should be relaxing. This trace bioelectrical activity disrupts coordination between muscles and makes the body fight itself. This reduces speed and is the main reason of serious injuries and muscle tears, according to Prof. Yuri Vysochin.

This “driving with the brakes on” obviously demands more energy. But the constant tension also hampers circulation and limits the aerobic metabolism. Glycolysis gets out of control and acidosis sets in, with a long list of problems.

To make the matters worse, all these bad news further excite the CNS, feeding a vicious circle. Like a fly in a web, the more it thrashes, the worse things get…

When a mere mortal equipped with a “hyper” nervous system and muscles that fight themselves ends up in a stressful situation, his performance—speed, power, coordination, endurance—rapidly tanks.

In contrast, a high performer relaxes when the going gets tough. His CNS gets inhibited sharply reducing any trace bioelectrical activity in his muscles. As a result, the speed of muscular relaxation dramatically increases—up to 70-80%!

These extended relaxation pauses give the muscles more time to rest and the blood vessels more time to deliver oxygen and to remove waste. The engine is purring, the plumbing is humming… Energy production demands plummet, manifesting in a decreased heart rate, respiration rate, blood pressure, lactate and stress hormones levels. The entire organism’s efficiency goes way up and the work capacity with it.

The second reaction, seen in athletic and military elite, is a manifestation of the relaxation mechanism of acute defense mobilization against extreme stimuli (RMAD) discovered by Prof. Vysochin.

You have heard another name for this phenomenon—the “second wind”.

Time to get RMAD!

RMAD is not just about endurance. The “second wind” is a generalized reaction that improves your tolerance to all sorts of stressors: exercise, hypoxia, hypothermia, etc. RMAD will make you “anti-fragile”.

Many people strongly manifest the “hyper” reaction, a minority (including most elite athletes), the relaxation reaction, with the rest somewhere in the middle.

The great news is, Russian scientists concluded that these adaptation types are not genetically predetermined and can be changed by training.

It takes a special combination of stimuli to cause an acute relaxation reaction. Repeated enough times, the reaction becomes long term.

Ideally, an athlete should aim to develop the relaxation adaptation type as early as possible in his or her career. In other words, you do not have to wait until you are “strong first” before you start practicing being “relaxed second”. For best results, tackle both at once, the Yang and the Yin.

Breathe less for greater performance and health

One of the most powerful stimuli for developing RMAD is hypoxia/hypercapnia: less oxygen and more carbon dioxide. Precisely calibrated; undisciplined breath holding might do more harm than good.

Soviet scientists discovered that hypoxia is a powerful training stimulus for improving athletic results. And more than that: training in the conditions of mild oxygen shortage improves resistance towards a variety of pathogens, from blood loss to radiation. One Russian scientist summed up that hypoxic training promotes “an increase in organism’s compensatory reserves, a perfection of health mechanisms”. Another concluded that, “Hypoxia is… a universal general cause of adaptation”.

Counterintuitively, hypoxic training improves oxygen supply of tissues, oxygen utilization by cells, aerobic metabolism. Hypoxia is “at least partially responsible for… increasing muscle mitochondrial and capillary density.”.

Hypoxia/hypercapnia can be induced by expensive or impractical means like high altitude and special devices—or simply by breath holding and voluntarily reduced breathing—hypoventilation.

Russians pioneered hypoventilation training back in 1967 and have done a lot since then. In 2015 pre-eminent sports scientist Prof. Nikolay Volkov flat out proclaimed hypoxic training to be one of the priority methods for world’s leading runners.

Noticeable improvements are seen, even in highly trained athletes, after just a month of introducing hypoventilation.

For instance, in a four-week experiment swimmers breathed less during 25% of their swimming training load. They were tested on veloergometers—to make sure the improvements had nothing to do with technique. Consider their improvements after a month:

- Power during a maximal load to limit time to exhaustion +21.8% (compared to +1.1% for the controls)

- Blood lactate after the test -27.5% compared to the control group

- Oxygen utilization co-efficient +11.2% (while the controls’ decreased)

In another experiment after weeks of veloergometer training with multiple breath holds athletes were able to perform a standard load at a lower heart rate and with a decreased glycolytic contribution.

Interval hypoxic training increased the glycolytic loads the athletes could handle—without an increase in blood lactate! Their alactic power also improved.

Russian scientists concluded that hypoxia tolerance is an integral indicator of how fine-tuned the organism’s regulatory systems are. (this has tremendous implications for “health training”.)

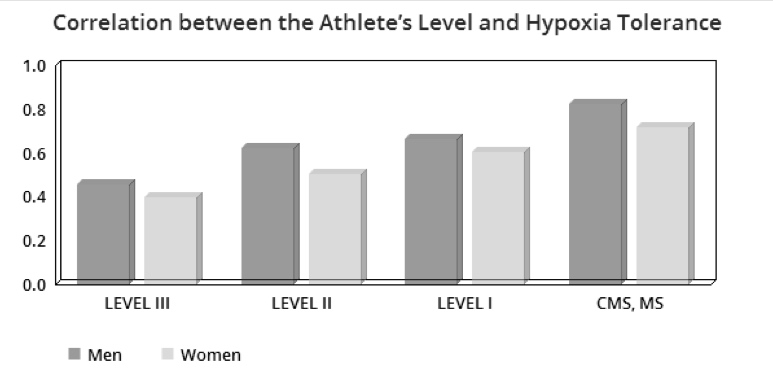

And that it tightly correlates with athletic performance. In a study involving 170 women and 154 men, athletes of different levels (from low intermediate to advanced) and from a range of sports established a direct statistically significant correlation between the athlete’s level and hypoxia tolerance:

Breath holding is not for amateurs

But before you cut back on your breathing, you must understand that it has to be done right.

On one hand, there are all these remarkable performance benefits just mentioned (plus various therapeutic effects in a variety of conditions and diseases, including serious ones).

On the other, “…any pathological state is directly or indirectly related to the… oxygen budget disturbance.” Bursts of free radicals produced as tissues get reoxygenated following hypoxia are a part of that story.

The dose makes the poison. Consider that while properly timed exposure to moderately high altitude is favorable to health and performance, going too high and/or staying there too long has opposite effects. Sherpas have a surprisingly low mitochondrial mass. After a two-month Himalayan expedition the concentration of products free radical damage in mountaineers’ muscles went up by 235%.

In other words, hypoxic training must be done according to the standards established by specialists, not haphazardly (“I can hold my breath longer than you!”).

And even some professionally developed hypoventilation systems are not optimal for athletes. For instance, one respected method was developed by an MD for medical, rather than athletic, applications. A number of coaches have discovered that, for all its benefits, this popular method reduces the lung capacity, which is unacceptable for athletes.

In addition to developing the breathing skills, an athlete who aims for the top must strengthen and condition his respiratory muscles. Because in metabolically demanding exercise they use up to 20-25% of the total oxygen consumption, training the diaphragm & Co. could make a difference between winning and not even placing.

Conditioning your breathing muscles has another, unexpected, benefit. Research has demonstrated that the rate of perceived shortness of breath very tightly correlates with the rate of perceived exertion—and that strengthening and conditioning the respiratory muscles reduces the RPE at the same work intensity. That means a greater output at the same effort.

(originally posted at: https://www.strongfirst.com/second-wind-pavel-information/)

Lessons from the Masters (IV): Pushhands

PUSHHANDS

A competitive mindset arises for many people as soon as they start to do pushhands. They want to avoid being pushed by their partner at all costs, and will do everything they can in order to get to push themselves. It is the exact opposite of what you should do. Remember, in Taiji you never meet hard with hard. In your form, you train using minimal muscle power to the greatest effect. You should continue doing this in pushhands.

Taiji master Zheng Manqing often said: “You must invest in loss.” This means that you must accept the push without offering resistance. You must follow your partner’s push and thus develop the ability to yield.

Yielding

To yield is to follow, to give in. When you yield, you accept your partner’s push and follow the direction of the force. At no point do you resist the push, but stay connected to and follow it. You must “Invest in loss” I.e. allow yourself to “lose”, to move backward and accept your partner’s push. If you don’t and instead try to resist your partner’s attempt to push forward, it isn’t Taiji anymore. Remember, your base – hips and legs – move you backward, with the rest of your body balanced on top. You do not just bend your upper body backwards while the legs stay still. If you do, then you are already violating one of the basic principles of using your whole body as an integrated unit.

When Taiji is used for self defence, we never meet hard with hard. For most people this is one of the hardest things to get used to. If someone grabs us, it is natural to tense up and resist. In Taiji, we do the opposite: Relax and follow the direction of the movement. It is said that “softness overcomes hardness”. You will not do that by resisting, but by accepting, connecting and relaxing. By yielding you follow the direction of the force – extending it – and thereby lessening its power. When you can’t yield any further, it is time to neutralize.

Neutralization

Neutralization is best described as changing direction and dissolving. When you yield, you can extend the force and decrease it somewhat. However, it is still targeted on to you. When you neutralize, you change the direction of the force and dissolve its effect. From here, the force goes through your body into your feet and into the ground (in the beginning, later you only take it to dantian). If this is done correctly, you now have complete control over the situation. You can send the force back towards your partner. You can issue.

Issuing

To issue means to release or return. Once you have extended (yielded) your partner’s force and neutralized (changed direction and dissolved) it, send your partner’s own force back towards him. You do not do this by tensing your muscles and pushing back hard. On the contrary, you allow the force that you have yielded and neutralized to return to your partner. You do this by being relaxed in your body and sending melting sensations in a continuous flow down toward your feet (later dantian, and instead of melting, you expand like a balloon). Issuing – returning – your partner’s force can be difficult to understand. When a skilled Taiji practitioner does it correctly, it looks like magic or a rehearsed play. Neither is of course the case. It is the natural result of a well-trained, integrated and well-coordinated body, a relaxed mind and coordination between mind and body.

There are no shortcuts in learning how to issue. Your form is your alphabet, your scales. There are many who would like to learn this “supernatural force” when they start to learn Taiji. Rarely do they continue for long. Taiji requires patience and an understanding and acceptance of the process involved.

“It is three times harder to learn to yield than it is to learn how to neutralize and issue”.

Yielding is the main process of the above three. If you are not able to yield, you will not be able to neutralize and there will be no force to return. According to my teacher, Master Sam Tam, it is three times harder to learn yielding than it is to learn how to neutralize and issue.

In the beginning, there will be a clear distinction between when you are yielding, neutralizing and issuing. Later this gap will become smaller, and in its most sublime expression completely disappear. It will all take place simultaneously. This is where it looks magically: Sending an opponent away without any obvious movement. The processes, previously described, have all taken place. They have merely been refined.

Not everyone who trains Taiji wants to work with pushhands. As justification, it is often said that the self-defence aspects are not interesting, and therefore pushhands is not something they wish to spend time working on. It is clearly a mistake and usually based on a lack of understanding. Pushhands is not just for people interested in self-defence. Pushhands can and should be seen as a tool for understanding your form better. Your partner helps you feel and sense your movement and your body on a deeper level. You learn to decode your body and mind, keeping both from tensing up in stressful conditions. This means that you, even more so than through the form training, will be able to relate your Taiji practice to your daily life, where you must constantly relate to outside forces, both at work and in private life.

Yielding – in Taiji and in life

Yielding is one of the key elements of Taiji. In relation to the self-defence aspects, but also – and in particular – in relation to daily life.

On a physical level, you move in the direction that the force comes in while you stay connected and centered. One of the biggest challenges in this regard is to sense exactly which direction a given force has. Be off-line by just a little bit, and you will end up resisting and thereby doing the exact opposite of yielding. Yielding requires sensitivity to learn. In the system of master Sam Tam, we have some partner exercises, which according to me, are the best ones to develop that skill.

Relaxation is the foundation of yielding and allows you to receive and follow the direction of the force, and thus avoiding a conflict. Both in regards to self-defence and everyday life interactions with other people.

Some people equate yielding to being weak, and they do not think that the real world leaves time and space enough to yield. Nothing could be further from the truth.

First, that assumption most likely occurs as a product of internal tensions and uncertainty, as well as an inability to yield at the right time, which requires timing. Secondly, once you have developed your ability to yield, you will find that you neither need space and time – you can yield anywhere and at anytime.

At the internal level, remove all intention and tension from the part of your body that is exposed to a resistance or force. You “empty” your body at the contact point, removing the power, so that it disappears from your center and your body into the ground. In the same way as water is drained out of a bath with increasing speed.

Both physical and mental yielding is needed. As a beginner, you will first learn the physical part. Later, internal yielding and gradually emptying will take over.

External and internal martial arts

External martial arts are, roughly put, based on the energy produced by movement, where the internal arts are based on the movement of energy. The external martial arts are based on strength and movement, the internal on awareness and immobility. The external martial arts are based on the idea of the best defence being an attack – the internal on the best attack being a defence. In the external martial arts, a blow is designed to penetrate the opposing defence, no matter what the opponent does to block it, and is therefore independent of the opponent. In the internal martial arts, the practitioner uses having control over the opponent’s strength, responds to an action made by his opponent, and is therefore dependent on the opponent.

Push Hand and competitions

If you use force – you lose (the) force.

– Sam Tam

The growing number of push hands competitions seen around the world is a misguided development. It is a very common misconception that pushhands is the self-defence aspect of Taiji. Nothing could be more wrong. Pushhands – or the more correct translation – sensitive hands – has in fact very little to do with pushing. It is about practicing your sensitivity to another human being and external forces. There is obviously an aspect useful for self-defence in becoming more sensitive – and there is especially a philosophical aspect that affects and changes the way you interact with other people.

Push Hands is not the strong overcoming the weak; the fast beating the slow. It is at odds with the underlying principles of Taiji: “The weak can overcome the strong, the old can overcome the young, and the woman can overcome the man.” Now that is a self-defence art – the opposite part is simply a fact of life and not worth spending 30 years training on!

Furthermore, a mediocre wrestler or sumo wrestler would win the majority of so-called pushhands contests, where technique, body weight and muscle strength are at the forefront.

Taiji is – if learned properly through a competent teacher and a good system – one of the very best self-defence systems. If it is learned from an incompetent teacher and a poor system based on brute force, it is one of the worst.

Taiji develops over time through continuous, diligent and proper training of the basic principles. It is not so much about acquiring many techniques; it is more about letting go of tension and reconstructing the body and the mind. And that takes time.

Pushhands exercises

There are hundreds of different pushhands exercises. From stationary to mobile, from pushing directly on the body to exercises where it is either one hand or both hands that are pushed on.

The whole idea of having predetermined patterns in pushhands is that it provides a method through which you can practice fundamental principles. Initially, single-handed pushhands exercises are used to understand and train the different circles, and achieve some basic ability in not providing any resistance yet being connected to the opponent (sticking). Next comes double-handed pushhands, where the same things are developed and further refined. And for both single- and double-handed pushhands learning to feel the direction of the force ( 8 out of 10 even experienced practitioners don’t do that!).

In the beginning, work slowly and with big circles, and in order for development to take place it is important that you cooperate with each other. Later, the circles get smaller and the pace can be either fast or slow. From there you move into more freestyle pushhands, i.e. there is no predetermined patterns, you only need to be sensitive to one another and work on moving away from action/reaction towards responding.

Sensitivity

Pushhands exercises are, as mentioned before, a way to develop sensitivity. Often when I introduce push hands exercises to new students, I start with exercises where there is no focus at all on pushing the other person or trying to find the other’s center. Instead, they focus on being sensitive and aware. If I say to you: “Relax your shoulders”, it may be difficult for you to feel your shoulder, and therefore close to impossible to relax it. But if I put my hand on your shoulder, then you have something useful to guide your intent. A partner exercise where you carry your partner’s arm with both hands and move it around in different positions is a good place to start.

First, you ask your partner to let you carry the whole weight of his arm while he lets go. Then move your partner’s arm around in different positions and at different speeds. If you sense that your partner would like to control or move the arm himself, you can change the tempo. If you find that he tenses or holds the arm up, you let go of it so it falls down. At first, move your partner’s arm around in positions lower than shoulder height, where it is easier to let go and feel gravity, then you move up to higher positions, which are more challenging for the shoulders, and where most people find it difficult to let go. Your partner is forced to direct all his attention towards his arm, bringing it into his consciousness via the sensory nerves and via the motor nerves telling himself to let go of all action and movement. The contact and the movements are made conscious.

Later – with more practice – it will all take place as an automatic, natural response. It is a bit like learning to ride a bike: First, it requires deep and focused concentration and lots of energy, but once learned, it is done automatically and does not require much energy.

Intention versus attention

Once you have an intent to do something, then your attention (awareness) is busy and you will not able to “listen” to your partner. For many, what happens when they train push hands is that they mistakenly become so focused on pushing and winning that they completely forget what pushhands is all about: learning to listen to your partner, sensitivity, noting the direction of the force, relaxing the body, etc. If you are focused on doing something specific (like pushing), you cannot simultaneously be fully attentive and responsive.

To train your intention and to have a strong intention is fine when you want to develop certain things – for example certain mental imagery or release internal force – Fajin – in a certain direction. However, when you are training pushhands exercises with a partner, it is far better to dial down your intention and increase attention.

Tension, yielding and neutralization

External or superficial tension in the muscles often has its origins in external conflicts, where inner tension comes about from inner conflicts. Internal tension prevents deep relaxation, making it difficult to learn yielding. Profound relaxation is the foundation that creates the opportunity to learn yielding and later neutralization. Small babies obviously do not have much inner conflict and therefore no inner tension. There is a saying in Taiji: “Become like a child again.”

Yielding – true or false?

One of the major obstacles in the development of genuine yielding is – yourself.

At a conscious level, there can be a great desire to learn yielding, but on a subconscious level, the reverse may be the case. For example, after having felt Master Sam Tam many people express, that they really want to learn to yield as he does, but they are unaware that the real motive behind their desire to learn yielding is that they just want to win. This inner – perhaps unconscious – conflict means that it will never be possible for them to master it.

Elastic strength

In most external self-defence systems and most sports, the primary focus is on developing muscle strength. In the internal martial arts, we aim to build elastic strength through our connective tissue, tendons and fascia. We develop this elastic quality throughout our body and frame, so that we are able to absorb a push or blow and subsequently return it to our opponent without any physical action from our side. When our connective tissues, tendons, and fascia stretches, they subsequently return to their starting point, and thereby send our opponent back in the direction from which he delivered his push. Just like a trampoline.

Sticking

Learning to stick is an essential part of your pushhands-development. Without the ability to stick you will never be able to develop yielding, neutralizing or issuing beyond a very limited level. The moment you make contact with your partner, stick to him like glue or like two magnets where the poles fits.

Your partner can feel you, but not push you. Just follow your partner’s push in whatever direction it might come. You provide no resistance at any time. You maintain contact right up until the point where you have issued or returned your partner’s force. Only then do you lose contact. It is impossible to learn to stick if you have not first developed your sensitivity up to a certain level and are able to yield without either offering resistance or collapsing your structure.

Remember, yielding is neither to resist, nor escape. Yielding is to follow the direction of an external force, extend it and gradually dissolving it until neutralizing it. You can only do that effectively by sticking to your partner.

Uprooting

In pushhands, you will always uproot your partner before issuing. You can compare it to removing weeds. To succeed, you must catch the roots. You uproot by first yielding and neutralizing your partner’s power and connecting to his center. Then you issue. Both your partner’s feet lose contact with the ground when they are uprooted, and he is sent back through the air in the direction that his push or force came from.

I remember many training moments with Master Sam Tam, where he, while sitting at his computer with his back turned, suddenly says to me: “You’re doing it wrong. You don’t uproot.” If you practice in front of a mattress hanging on a wall, you can hear from the sound your partner makes when he hits the mattress, whether he has been properly uprooted or not. Properly done, the partner will fly through the air. If not, he will just stumble lightly or take a step backward, one foot constantly in contact with the ground.

“Fill up the gap”

If your partner in pushhands suddenly collapses his structure when you try to issue, and quickly pulls his arms towards himself close to his body, follow immediately and “fill up the gap”. When you start training free pushhands, where there is no fixed pattern, you will from time to time meet people who collapse and think that it is yielding. It is not, and in a real confrontation with another person, it would be a disaster!

I remember one of my former teachers, Master Yek Sing Ong, telling me one of the first times I got the opportunity to train free push hands with him, that I should always imagine that my partner’s hands were knives. You do not want two knives to get close to your body!

On another occasion, several years later, during one of my first visits to Master Sam Tam, I tried, in frustration over not being able to yield properly, to collapse. Immediately – which he later explained – he chose to fill up the gap and placed his hand around my throat as were he a pittbull. He stressed that I should never use a substitute method in a vain attempt at “winning” and that it would have disastrous consequences during a real confrontation with another person. I should always do the right things – yielding, sticking, neutralizing – even if it did not work right here and now against him. Like a bow is stretched and unstretched but does not collapse, we too do not collapse when yielding.

“Substitute method”

“I’m not a meat rack, why do you hang your meet on me?”

– Yang Chengfu

In addition to collapsing, there are many who use other unintended solutions in free push hands, violating all the fundamental principles of Taiji. They focus on not losing, rather than on learning. It is possible that they manage to train the principles, as long as it is in predetermined movement patterns, but as soon the switch to free push hands occur, they forget all about it. They lean their entire body towards the partner and use their bodyweight, or they use segmented force where they push with their hands, use arm muscles or they choose to “noodle”.

“Noodle”

“Noodle” is a term that is often used for people who violate more or less all Taiji principles when they train pushhands: Everything from the straight back to being connected in the body and everything in between. Just so that they can remain standing on the square their feet are planted on, as were they defending a piece of land. They can be difficult to push if you use brute force. However, if you do not succumb to the temptation of using strength and power – and of course you don’t, why else learn Taiji? – but instead use sensitivity, sticking, awareness and sink the qi to dantian, you can walk right through them.

If they start to “noodle”, then immediately stop having any power whatsoever in your hands. Just maintain a connection through touch. When they subsequently move and try to escape, they end up tensing their muscles, and then you can move them completely effortlessly. Or as Master Sam Tam puts it: “The noodle becomes spaghetti before cooking.”

Various training partners

It is important to have good training partners, if you want to grow and develop your skill. And it is important to train with different people. By training with partners who are more experienced than you, you get the opportunity to follow their movements and experience their quality. Allow them to move in any direction they want, but try to follow their movements without resisting while remaining centered. Do not “noodle”. Be sensitive.

Training with someone who is less skilled than you are, on the other hand allows you the opportunity to experience what it feels like when you perform the movements correctly and with relative ease can control your partner. It allows you to experiment, making small improvements and refinements. You have to trust the process and the relaxed state – otherwise you risk being tempted to use brute strength and lean your bodyweight toward your partner, should he tighten up or block, while you lack the inner strength needed to move him. It will come in time – if you trust it!

Training partners you should kindly reject are those that continually correct you. One moment, they do everything to ruin the drill, using physical strength and resistance. The next moment they jump backward just by a small touch of your body or arm – of course after having corrected you based on how they think the exercise should be performed. They rarely have time to listen to the teacher’s instructions and directions, and are more concerned with their own ideas and showing everyone how talented and clever they are. There is often no hope of any real learning or development taking place, and you are wasting your time practicing with such a person.

Stretching muscles

When a muscle contracts, it gives power in the same direction as the movement is performed. Stretching of the muscles on the other hand produces force in the opposite direction of the movement. In relation to Taiji and push hands, it means that when one partner pushes in on you and you simultaneously stretch and expands, you will yield and return at the same time. The prerequisite is a relaxed structure, where there is both something stretching, and at the same time something giving a frame. As the classics say, “like bending the bow and shooting the arrow.”

If, however, you tense up your muscles, you will “lock” the power inside your own body, stiffen, and will only be able to move your partner by making a weight shift or by pushing hard in front of you with the use of chest, shoulder and arm muscles.

Issuing

“To draw the bow and shoot the arrow.”

There are several ways to issue. The two most useful ways are from the feet and from the center. As described in a previous newsletter, issuing from the feet is slower than doing it from the center. On the other hand, there is great risk that you are going to tense up and use physical force when issuing from the center and expand simultaneously. I would suggest that you learn to relax, sink and empty, have a fully integrated body with a relaxed structure and is able to take all the power from your partner’s pressure on your arm or body into the ground before you train issuing from the center. Without structure, no elasticity!

Your center – in regards to pushhands

At the beginning of your Taiji training, you have no idea of where your center is – at best only an intellectual understanding. Therefore, great time is spent on various exercises and standings to find and feel your own center. If you train push hands with an experienced partner, he or she, in turn, easily finds your center and thus the opportunity to uproot you. Gradually you develop a sense of and contact to your center. It feels large and you begin to sense that all movements originate from here. Later on, you experience moments of being connected to your center, and later yet you will always be centered. Your body will feel like a big ball or balloon, with your center as the center of all movements in any direction.

Your training partner will have a more difficult time finding your center, where you in turn find it easy to find his, connect it to your own and thereby be in complete control of him in any situation. For your training partner, your center has changed from being huge and easy to find to being small and, at best, impossible to find. For you, your center has gone from being something you could not even find to something feeling big and covering your entire body. As a babushka-doll in a ball edition: Beneath the big ball is a smaller ball, and beneath this an even smaller ball and so on. And at the center of all these is your center.

Timing – with respect to a partner

There are several aspects to training timing. At the physical level, there is our own sense of timing regarding our own body during movement – as an unbroken line from feet to fingertips. The different body parts should be balanced and integrated. Next, the body must be as relaxed as possible so that energy can flow freely and unhindered – guided by our Yi. The same adjustments should be made when engaging a partner, and we have to blend and interact with him. Are we too fast relative to our partner, we lose the connection. Too slow and we resist.

Through our partner exercises we are able to develop our sensitivity and experiment with timing in different ways. In this regard, the partner is of great importance. The partner should be interested in cooperating and developing the material – otherwise it will be very difficult. Master Sam Tam once said to me when I told him that I felt privileged to have good partners to work with:“Up through history, they all come in pairs.”

The importance of having good training partners and to create an environment without competition, but with a focus instead on learning and developing, cannot be overemphasized.

Once you have developed some understanding of the basics and have begun to experience the positive aspects of improved timing and sensitivity, it is time to practice with as many different people as possible. Different people react differently, and once you feel that you have a foundation to work from, you should develop yourself further by crossing hands with as many people as possible.